CHALLENGE

A high-stakes MVP

Designing an MVP sounds simple. But in high-pressure environments—especially in government—it’s one of the easiest places for things to go wrong.

Teams often treat the MVP as a stripped-down version of the final product. Stakeholders push to include every possible feature users might need, “just in case.” Delivery teams scramble to test feasibility, compliance, policy alignment, user needs, and operational handoffs all at once. Decisions pile up fast. Assumptions go untested. And what started as a minimum viable product turns into a maximum viable compromise.

The result? Delayed releases. Burned-out teams. A product that’s overbuilt, under-validated, and vulnerable to failure the moment it meets the real world.

We had just four months to avoid that fate. Four months to define a smarter MVP—one that balanced user needs, technical feasibility, and legal requirements without collapsing under the weight of good intentions. We weren’t just shaping a product; we were de-risking a multi-million-pound concept, under tight scrutiny, with global implications.

CONTEXT

To turn policy into practice

Under the Environment Act 2021, the UK introduced landmark legislation to curb illegal deforestation linked to agricultural commodities like palm oil, soya, cocoa, and cattle. The goal was bold: hold businesses accountable for their supply chains and require them to submit environmental due diligence reports. But the reality on the ground was messy.

Most businesses had no idea they were exposed. Supply chains were tangled, opaque, and international. Reporting requirements were unfamiliar, especially for non-financial data. And the stakes weren’t just regulatory—they were political, global, and environmental.

To turn policy into practice, the UK government began building a first-of-its-kind digital compliance service. One that needed to be intuitive, enforceable, and scalable across a fragmented landscape of importers, manufacturers, and brand owners. Our team was brought in to define the MVP and build the service that would take this idea into private beta and shape the foundation for a national service.

APPROACH

A stress-tested, user-informed and evidenced MVP

To break the cycle of overbuilding and under-validating, I introduced the team to a RAT mindset—Riskiest Assumption Testing.

The RAT approach flips the typical MVP question from “What should we build?” to “What must be true for this product to succeed?” It forces teams to name their blind spots—the assumptions that, if wrong, would derail the entire concept. Things like “users will upload this document here”, “they’ll understand the rules without guidance”, or “this system integration will be ready in time.”

By shifting the focus from delivery to de-risking, RAT turns MVPs into strategic probes. They become learning tools, not early versions of the final product. Instead of loading up features based on hope or politics, we design experiments to test reality—quickly, cheaply, and with purpose. That mindset unlocks faster pivots, tighter decision-making, and ultimately better products.

To make this practical, I designed a three-workshop sprint involving our full cross-functional crew—design, research, policy, tech, data, regulators, and delivery leads.

- Workshop 1: The Unknowns

We mapped the full end-to-end service and had every team member list out unknowns. We used a triangulation method—each unknown had to be framed as:- The assumption

- The risk if it’s wrong

- And any existing evidence

Most assumptions fell into three buckets: user behaviour, technical feasibility, or organisational decision-making.

- Workshop 2: Mitigations

We then brainstormed what tasks would increase our confidence. This step was crucial—it revealed the real effort required to validate assumptions and helped the team understand that MVP scoping wasn’t just design work, it was about coordinated testing, internal alignment, and readiness across the board. - Workshop 3: Prioritisation

I then ran a smaller prioritisation session with leads and the service owner. We used a mix of team sentiment, critical path logic, and structured frameworks to determine which assumptions posed the highest risk and needed to be addressed before build.

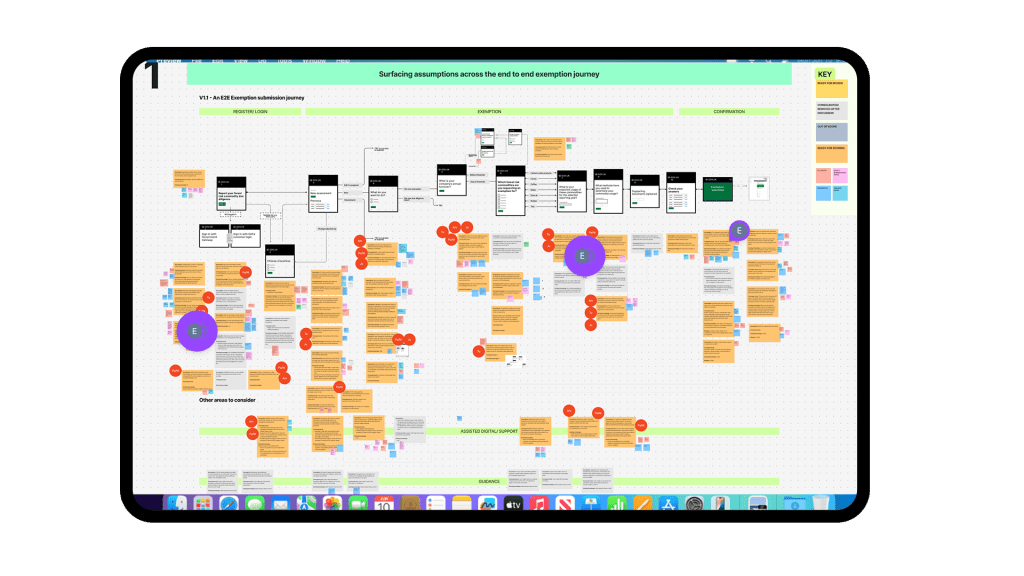

Fig.1 – Sample visual of the assumption listing workshop across the proposed end to end journey

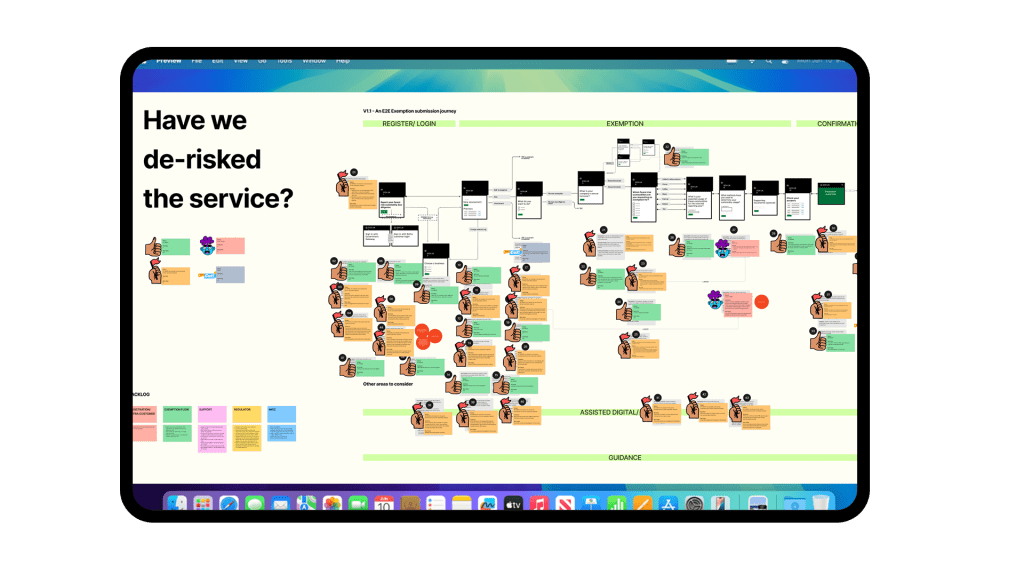

Fig.2 – Sample visual of assumptions with mitigation tasks and votes

From these sessions, I created a prioritised backlog of risky assumption tasks with owners assigned. These were tracked across sprints leading up to the GDS Alpha assessment.

As we worked through them, critical improvements emerged:

- User Journey Fixes: e.g We learned that front-loading compliance guidance overwhelmed users. We redesigned the journey to stagger content and introduce helper text at key moments, improving comprehension dramatically.

- Technical Constraints: e.g We discovered key blockers—like the proposed user registration model being unviable within the timeline. So we pivoted to a proven, reusable registration component already in use by other government services.

- Design Iteration: As confidence grew in certain areas, we revised whole segments of the journey—trading in theoretical flows for tested ones backed by user evidence.

Fig.3 – Sample visual of risky assumption reporting to track progress

By the time we hit the Alpha assessment, we weren’t just showing a concept—we were presenting a de-risked, validated MVP. One that had been stress-tested, user-informed, and backed by cross-team confidence. We passed the assessment, secured approval to build, and gave stakeholders something rare in complex service development: real confidence in the path forward.

OUTCOMES

A departure from headline metrics that don’t say enough – Product and service owners need meaningful insights

No More Fire Drills

By tackling risky assumptions upfront, we avoided late-stage reworks and firefighting. The team stayed focused, and delivery moved smoothly.

£600K Risk, Dodged

Without a validated MVP, failing the alpha assessment would’ve triggered a costly extension—£400,000–£600,000 in extra time, staffing, and delay. We didn’t just avoid it—we made it obsolete.

From Opinion to Evidence

The final MVP wasn’t built on instinct—it was built on insight. Every decision had rationale, every feature had purpose, and the whole team knew why we were building what we were building.