For the last eight years, nearly every project I’ve worked on has kicked off with the same request: “Can you map the stakeholders?”

So I do it. I spend hours building the web of influence—execs, delivery leads, backend devs, the policy owner who signs off on updates, the support staff fielding user complaints. I build a (beautiful) map. I present it. The team nods. Then it’s filed away in some forgotten folder, never to be referenced again.

The irony? The task was never just about mapping.

It is about understanding the universe around a service—and then working with that universe to build something that holds up in the real world.

This is how I came to think more deeply about stakeholder capitalism, a term I first encountered not in a design book but through reading about Sol Price, the founder of FedMart and Price Club. He believed in putting employees first—not as a perk, but as a strategy. Employees weren’t just a resource; they were partners. That same thinking applies when we’re designing or reinventing services. If you want something to succeed, the people building, running, and maintaining it need to be part of its inception.

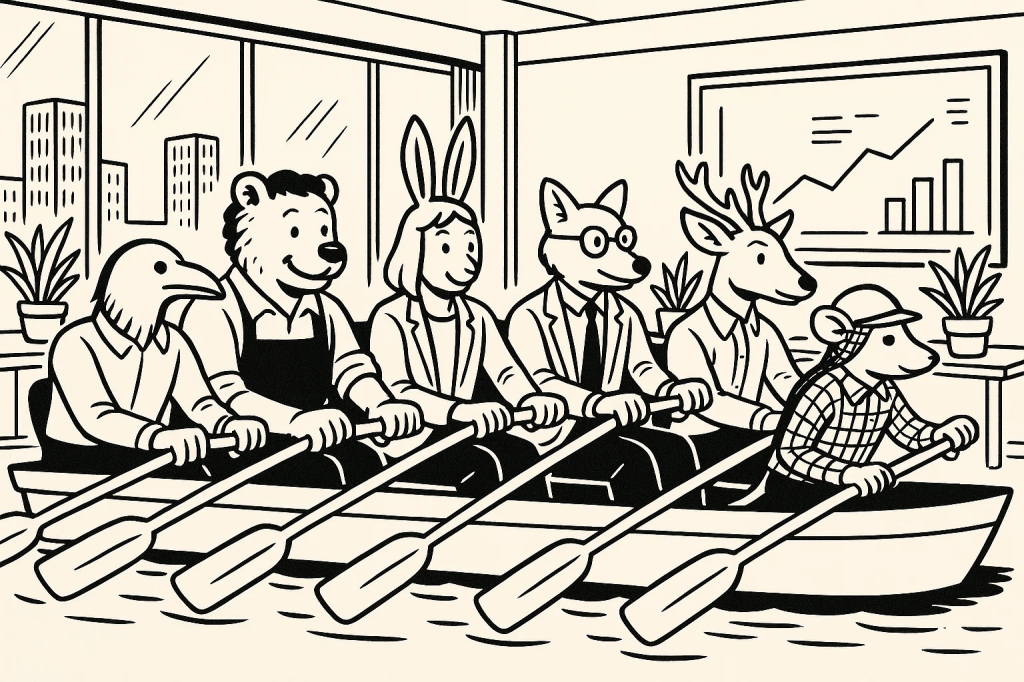

And I couldn’t help but see the connection. It’s the same mindset needed when designing services, features, policies, or platforms. You’re building with—not just for. You’re designing a system people will live inside, not just interact with.

What Is Stakeholder Capitalism in Service Design?

It means recognising that every service is embedded in an ecosystem of people, processes, systems, and trade-offs—and all of these need to be visible during design and decision-making.

It’s about asking:

- Who uses it?

- Who delivers this service day-to-day?

- Who maintains it, updates it, explains it to users, answers the phone when it breaks?

- Who funds it, approves it, operates it, and enforces it?

- Who suffers when it fails?

Too often, service design zooms in on the user and the product—but forgets the infrastructure, the staff, and the teams holding it all up. Stakeholder capitalism brings them all in. Not out of nicety or ritual, but because they’re the ones who turn ideas into durable services. When done well, it naturally de-risks your design—because you’ve already accounted for the human, technical, and operational realities.

What happens when this isn’t done?

Here’s some familiar(I assume) scenarios that pop up when stakeholder voices are missing:

- At a Grocery store: A new app is launched encouraging customers to “enhance their experience.” Problem is, they can’t actually make purchases on it—only the desktop site supports checkout. In-store, customers try to scan loyalty cards via the app, but it doesn’t work. Staff aren’t trained on it, so they manually type in numbers like they did five years ago. The app becomes another source of confusion, not clarity.

- On a Shopping App: A sleek feature to have AR pop ups of shopping baskets gets greenlit by leadership. Product builds it. Then the delivery team realises ops can’t support it, and compliance wasn’t consulted. Support teams are blindsided. It ships, but quietly gets buried six months later under complaints and unmanageable overhead.

- With an Airlines: A new self-check-in service is rolled out to “streamline boarding.” But airport ground staff are left out of testing. Systems don’t integrate. Queues get worse. Staff get blamed.

- At a High School: A new student portal is introduced without involving teachers or administrative staff. It looks great on paper but doesn’t align with how timetables, assignments, or attendance are actually managed. Chaos. But maybe it makes it easier to skip classes.

- At a Hotel: A hotel adds digital check-ins and keyless entry—but housekeeping and maintenance weren’t part of the process. Sometimes keys don’t work. Service tickets pile up. Rooms go unchecked. Reviews slide.

3 Practical Models of Stakeholder Capitalism when Designing Products & Services

While the term “stakeholder capitalism” is often used in macroeconomic and corporate governance conversations, its principles apply powerfully—and often underutilised—in the day-to-day reality of service design and delivery.

Here are three practical models teams can adopt to embed stakeholder capitalism into their project environments.

1. The Governance Model

Designing more equitable and effective decision-making.

At its core, the governance model seeks to democratise decision-making by ensuring stakeholders are not just consulted but actively shape the direction of a project. The simplest version of this is a “one person, one vote” approach, where all stakeholders have equal say in key decisions.

However, equal voting doesn’t always equate to effective outcomes. Not all stakeholders are equally impacted by or equipped to assess certain decisions. For instance, a tech lead will likely have a deeper understanding of long-term software feasibility than a policy stakeholder, just as a frontline staff member may have critical insight into operational bottlenecks that leadership can’t see.

A more effective approach is dynamic voting power: assign decision weight based on:

- Proximity to the decision – How close is the stakeholder to the day-to-day implications of the choice?

- Impact from the decision – Will this stakeholder be directly affected by the outcome?

- Expertise relevance – Does this stakeholder have specific knowledge that meaningfully informs the decision?

This model helps balance inclusivity with informed authority—enabling more robust, reality-checked choices that are less likely to fail in implementation.

2. The Participation Model

Ensuring the right people shape what gets built.

While the governance model focuses on how decisions are made, the participation model is about who is involved in shaping the service throughout its lifecycle—especially during discovery, design, and testing.

In practice, this means identifying and including the true service stakeholders—not just business owners or user proxies, but those who will deliver, maintain, support, or experience the service in reality.

For example, when designing a new customer support journey:

- Include customers, to understand their needs and expectations.

- Include frontline support staff, who deal with queries daily.

- Include backstage teams, who resolve escalations, maintain systems, or manage performance data.

Often, services are designed in silos and require elaborate change management efforts after launch. The participation model shortens that loop: by involving key actors upfront, the design reflects operational truths, and change is absorbed more naturally—because it’s already co-owned.

3. The Stewardship Model

Designing for long-term ownership, evolution, and resilience.

A common blind spot in many service delivery projects is the assumption that once something is shipped, the work is done. But services are living systems. They degrade or thrive based on how well they are stewarded over time.

The stewardship model ensures that:

- Long-term owners of the service are identified early

- Handovers are not last minute thoughts

- Clear responsibilities for maintenance, iteration, governance, and feedback loops are distributed and understood.

- There are mechanisms (not just inboxes) for service feedback to flow back to decision-makers and delivery teams.

For instance:

- If a chatbot is launched, who owns the content library and NLP training after delivery?

- If a new returns policy is implemented, who monitors its effectiveness across customer service, logistics, and finance?

- If a digital tool is deployed across multiple business units, who owns the cross-functional data strategy?

Stakeholder capitalism isn’t just about co-designing the “what”; it’s about safeguarding the “what next.” The stewardship model prevents services from becoming orphaned, under-supported, or quietly sunset due to neglect.

What It Looks Like on Real Projects

In my experience, embracing stakeholder capitalism isn’t neat. It’s a slog. Sometimes you have natural participation. Other times, it’s like pulling teeth.

Here’s what I’ve learned:

- Always start early. It builds healthy buy-in/momentum and makes it easier to expand as the project progresses.

- Some projects already have strong cross-functional engagement. Great—don’t overdo it. Just reinforce the alignment.

- Other times, I’ve spent hours scheduling calls, chasing people down, getting them into workshops, or just convincing a team to attend a user testing session.

- I’ve manually tracked decisions, flagged missing voices, and written the dreaded “Blocker” bullet for things I knew would come back to bite us.

- It can feel like too many people are in the room. One trick: next to each stakeholder, list their role, what part of the service they’re connected to, and who they rely on. You’ll quickly see who needs to be in which conversation.

- And sometimes don’t push it – pick your battles. I’ve learned to assess whether pushing for fuller representation will materially change the outcome. If it won’t, I (begrudgingly) let it go.

This work is rarely rewarded early on but it is always recognized towards the end. It’s invisible like most parts of a service. But the cohesion it creates shows up when things go live and don’t fall apart.

Final Thoughts: Less Idealism, More Intention

Stakeholder capitalism isn’t just a principle—it’s a working method for building services that survive the real world. It’s less about moral virtue and more about design maturity.

Not every project needs a stakeholder parade. But every service deserves to be shaped with a clear understanding of the system it sits in.

If you’ve ever seen a service collapse under the weight of its own blind spots, you know the cost of skipping this step.

So here’s a thought: next time someone asks for a stakeholder map, pause. Ask what universe this service lives in. Then bring that universe to the table—not just the ones with the loudest voices.